Home: News | About YEM | Why YEM

Countries: Algeria | Israel | Jordan | Lebanon | Libya | Morocco | Palestine | Tunisia

Thematic Priorities: Skills anticipation | Work-based Learning | Digital skills mainstreaming | Entrepreneurship skills

Knowledge Resources: YEM Skills Panorama | Country Profiles | Data and Statistics | YEM Publications | Other useful resources

Networking: Discussion Forum | Blogs and Thinkpieces | Youth Homepage | Members of the Community | Join the Community

Events: Overview | Final YEM Regional Forum (July 15) | YEM Regional Forum (April 8)

Read the insights and opinions of experts from the region and beyond on issues related to YEM Project's thematic priorities.

February 2020

Youth make up the majority of the population in the region and in a country like Jordan, where around 70% of the citizens fall under 30 years of age, this is a critical issue that must be addressed immediately (United Nations Jordan, 2019).

The youth unemployment rate in Jordan for the year of 2018 stands at a staggering 37.2%, which is noted to be one of the highest figures in the past 30 years and among the highest globally (The World Bank, 2019). This is even higher amongst vulnerable groups such as women, where despite having a slightly higher ratio of educated females to males in Jordan, the female labour force participation rate is at only 14% (ILO, 2017b). According to the World Economic Forum’s 2018 Global Gender Gap Index, Jordan has one of the lowest employment rates for women worldwide (World Economic Forum, 2018), suggesting that those females face more obstacles when attempting to enter the workforce than their male counterparts.

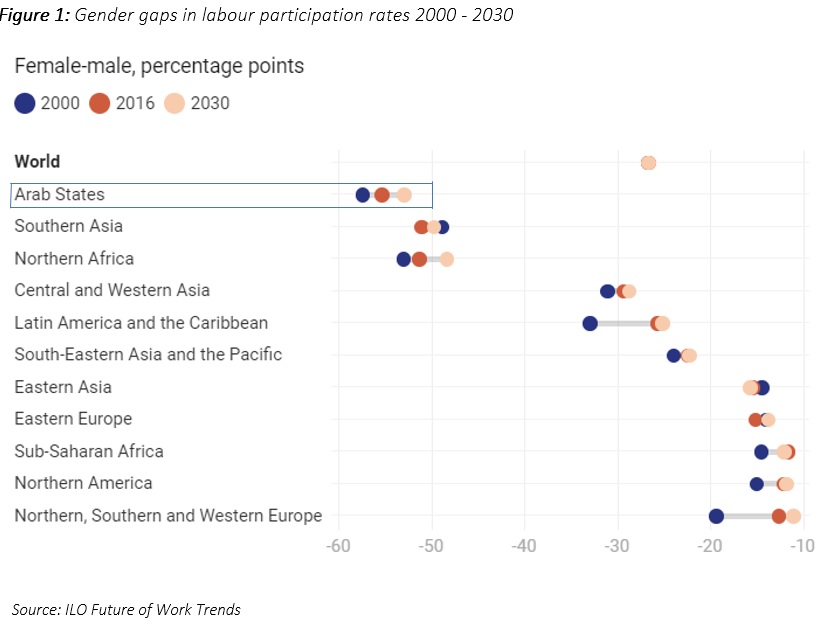

This is not just an attribute of the Jordanian labour market, but a common feature across the Arab States which has the widest gender gap in workforce participation globally at 55% (ILO 2017a). While various policies and reforms to alleviate this have been put in effect, the outlook shows marginal improvement.

Female youth employment in Jordan: Key Challenges

While it is often presumed that higher educational achievements lead to an easier transition into productive employment opportunities, this does not hold entirely true in the case of Jordan. Even in this case, females are at a greater disadvantage compared to the males. According to the Jordanian Department of Statistics, unemployment rates are highest among those who have attained tertiary education by 24% in comparison to other educational levels. The unemployment of males who carry a bachelor’s degree and higher is at 23%, while the same indicator is at 78.2% for females. Approximately 54.7% of the unemployed hold a secondary education certificate or a higher qualification (DOS, 2019). These figures indicate a great loss in the return on investment in terms of education for Jordan. Females may often find themselves confined to a limited range of occupations and places of work that are considered ‘acceptable’ due to various challenges. One of the main challenges for the country’s economy is to shift workers towards higher levels of the value chain as the transition phase from school to work can be extremely long. Based on surveys conducted on a national level, this transition can take up to 3 years (ILO, 2017c).

This can be attributed to a wide array of reasons, the most obvious one being the lack of jobs in the private sector. Job creation in the private sector within Jordan is still primarily in low-skilled jobs which, very often, does not match the expectations of Jordanian youth. For the year of 2017 alone, around 61,000 students have graduated from Jordanian universities. On the other hand, the total net jobs in both the public and private sector was only at 48,000 jobs, many of whom were not entry-level jobs that match these youth’s qualifications. Furthermore, out of these 48,000 jobs, only 16,000 required employees who had an educational background beyond high school (Ministry of Labour, 2017). This creates frustration among youth, causing many of them to either continue with further education or detach from the labour market altogether.

Another reason that contributes to further unemployment is the negative perception within the Jordanian population towards vocational training where its institutions are considered weak by many, as it is the stream that requires the lowest academic achievement. The negative stigma associated with certain jobs that are in the service sector or require a lot of physical labour, such as construction work, has left even more Jordanians unemployed (ILO, 2017c). These sectorial jobs are considered undesirable for men and are contemplated as unthinkable for women. This is one of the main reasons that the Jordanian labour market holds an estimate of 1.4 million non-Jordanians workers (Dupire, 2017).

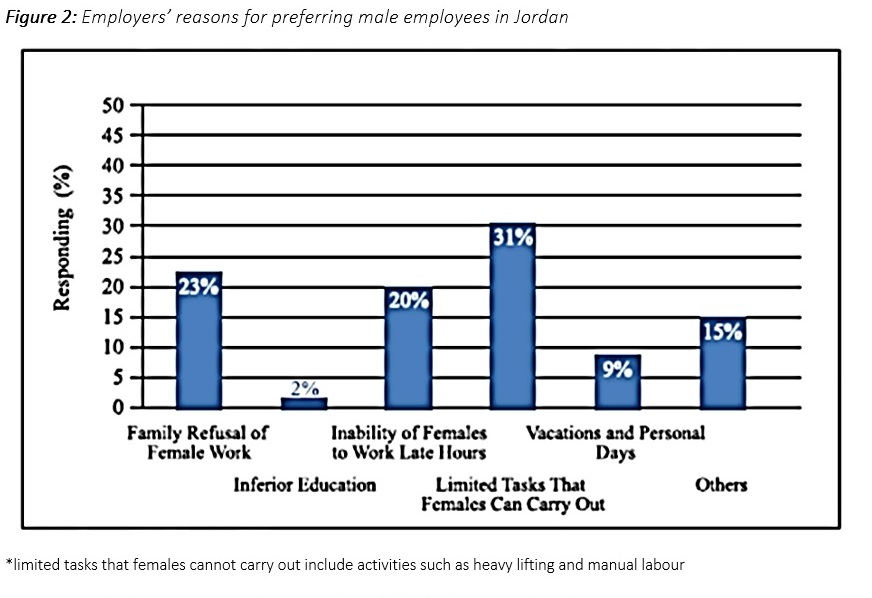

The way employers perceive females is one of the obstacles attributing to joblessness among Jordanian women. Women are perceived as a liability since they may suddenly leave their job and are ‘at the risk of being married at any time’. Employers tend to discriminate against females when hiring, because they view them as an uncertainty who may quit abruptly at any point, due to family obligations or even pregnancy. Studies have shown that employers in Jordan are much more likely to invest in building the skills and capacities of their male employees instead of their female counterparts, as they view their development as more long-lasting and sustainable for their firm (UNDP, 2015).

The consequences of these obstacles are a missed opportunity cost for the Jordanian economy that negatively affects its GDP. Tax revenues in Jordan convey that an average male contributes to around JD 33,000 in income tax throughout his life, on the other hand, an average Jordanian woman’s contribution does not exceed JD 4,600. Women’s absence from the labour market also further impacts poverty rates of households and increases dependency ratios (Alami, 2019).

Ensuring the mobilization of the second half of a very educated population in Jordan presents a huge potential as one of the key factors of economic stability in a dynamic region. No economy can advance to its full potential unless both women and men participate fully. Being half the world’s population, women have an equally important role in driving economic growth.

Grappling with the challenges

1. Raising awareness within the Jordanian society and on a grassroots’ level:

Without changing societal views regarding gender stereotypical constructs in terms of the ideal roles associated with masculinity and femininity, top-down reforms will have a limited impact. In order to battle these stereotypes and increase the rate of females participating in the workforce, advocacy and awareness campaigns by various stakeholders are vigorously required. Raising public awareness about the importance of a female’s role in her community not only as a mother, but also as a powerful economic actor and a leader is important. This can be conducted through the implementation of national public awareness programs that encourage dialogues within society to discuss the challenges females face, equity among both genders and the important role women play within their communities.

2. Increasing female representation in decision-making positions:

In order to challenge gender-pay gaps, occupational, and sectoral segregation, women must be in a position to influence and shape legislations and decisions. Improving female participation may first begin with increasing female leadership through targets, quotas and goals ensuring their participation on multiple levels within both the public and private sectors. High levels of civic participation generate substantial positive externalities in the form of greater economic participation which will be further reflected on an increase in the number of females in decision-making positions within the private sector as well.

3. Capacity-building and skills enhancement:

Legislation alone is insufficient to prevent and eliminate gender discrimination. Equal treatment mechanisms must be underpinned by effective remedies and the capacity-building of women, especially through targeted TVET programmes. This requires the cooperation of a multitude of stakeholders from different levels within the Jordanian society. Ministries and educational institutes should target and involve decision-makers within the private sector through policy forums and discussions regarding the challenges females face within the Jordanian labour market. This will assist in the creation of capacity-building programs that may include soft skills trainings, leadership trainings and mentorship to help enhance the skills of young females entering the workforce and help them cater to the needs of the private sector.

Collaboration among different stakeholders and building capacities will help in ensuring optimal utilization of human capital when the country reaches its demographic dividend. Partnerships between the government and educational institutes, can help in improving the quality of technical and vocational education and training among youth, with a particular focus on females, while providing them with skills that are in line with the private sector’s needs. The success of females in jobs stereotypically assigned as ‘masculine’ work, will help in battling occupational segregation and eliminating gender-biases when recruiting.

4. Public-Private-Partnerships and Gender Mainstreaming:

Negative stigma remains associated with women’s work in the private sector. Harmonizing working conditions within both the public and private sector will allow the families of females to view the private sector as a source of acceptable employment as well. This is essential as the public sector alone can no longer accommodate the large number of annual male and female graduates. Applying similar working condition requirements to both genders will remove the disincentives and additional costs of hiring a female over a male. For example, amending Article 72 of the Jordanian Labour Law to include entitlement to adequate on-site childcare facilities for both men and women who have children under the age of 4, will remove any extra costs associated with hiring married females, and will level the field for competition among both genders. Moreover, it will help in shattering embedded, society-wide stereotypes where females are viewed as the family’s caretaker, and childcare is solely seen as a mother’s responsibility. This allows women to continue their career within a company without having to leave work or lose years of experience to take care of their children, and provides private firms with a wider variety of male and female employees to hire from, as opposed to only choosing from a pool of candidates where half of the potential talent is excluded.

References and further reading